The Physics of the Mind Part 2

On a Newtonian Mind

In a past essay, we introduced the notion that your specific, personal experiences are governed by the same physical laws that appear in textbooks - like the mechanics of a ball rolling down a hill or the entropic nature of the universe. While it can be useful to treat physics as an abstract, external idea for the sake of learning, let’s spend some more time applying the laws of physics to your meaningful life.

First a quick history lesson. Starting way too late, the 16th century gave us great thinkers like Copernicus and his heliocentric model of the solar system, Galileo and his discovery of the Jovian moons, and Descartes and his Cartesian coordinate system. The discoveries from this time period enabled Isaac Newton to lay the foundation for modern mathematics and science through his laws of motion and invention of calculus. This was a major shift in thinking because he demonstrated that there were inert laws of the universe, independent of morality and human interaction.

Classical or Newtonian mechanics flourished thereafter by the ilk of Bernoulli, Euler, Lagrange, and Laplace. Skipping over discoveries surrounding electricity, magnetism, radioactivity, and thermodynamics; we arrive at the 20th century to the birth of Einstein and his theory of relativity which arose when contradictions were found between classical mechanics and electromagnetism. Einstein essentially found that time differs for objects moving at different relative speeds. As he stated inversely, "The basic laws of physics are identical for two observers who have a constant relative velocity with respect to each other."

Einstein’s special and general relativity theories paved the way for a new school of physics: relativistic mechanics. Relativistic mechanics shares similarities with classical mechanics in its study of objects in motion (kinematics) at rest (statics), but what is considered at rest or in motion depends on the motion of the observer - something not considered in classical mechanics.

Around the same time, Maxwell Planck kicked off a new field of physics through his quantum theory. Quantum mechanics shows us that subatomic states are bound to discrete levels of energy, momentum, and/or angular velocity rather than along a continuous spectrum like objects in classical mechanics. Physicists such as Bohr, Heisenberg, Pauli, Bose, and Schrodinger further developed it as an explanation for the way the world works at the atomic and subatomic scale. This led to groundbreaking technology like Oppenheimer’s atomic bomb and Fermi’s nuclear reactor.

In the late 1920s, Dirac began to apply quantum mechanics to electromagnetic fields which led to a harmonized view between quantum theories and Einstein’s special relativity. Quantum field theory became an official framework around 1950 when Feynman created a renormalization process that helped scientists work through calculations that kept leading to infinity, a clear violation of thermodynamic law. Feynman himself called renormalization a shell game, so it was supplanted by Schwinger’s source theory which could be used to reproduce Einstein’s results of relativity at a subatomic scale. Lastly, the Standard Model was able to explain electromagnetism, weak interaction, and strong interaction in a cohesive manner which was experimentally confirmed through the discovery of The Higgs Boson in 2012 by firing high energy particles at high speeds.

These progressions in physics do not invalidate previous findings from Newton and his successors. Rather, these physicists found inconsistencies under certain circumstances and tugged on those loose ends until they branched into a new, adjacent field of physics.

This diagram articulates which school of physics dictates how the world works based on the context - in this case, the speed and size of the object at hand.

Size and speed are two attributes of an object that govern the physical world, so we should find a suitable object and attributes that govern the behavior of the mind. Just like how a particle/wave is the most basic object governing behavior in the physical world, a thought is the most basic object governing behavior in the psychic world. If we categorize the ways thoughts are governed, it can be simplified to causality and scale.

Causality refers to our ability to trace the origins of an action, event, or thought. Applying this concept to the mind, a causal thought can be traced to a specific origin like a belief accepted from parental influence during childhood or an idea portrayed in a recently watched movie. An acausal event or thought is one in which the origins cannot be traced such as a synchronicity or the revelatory idea that hits us like a freight train in the middle of a mindless activity.

Scale is a much simpler concept. It answers the question on whether an individual or collective psyche is involved. Just like how a complex system becomes greater than the sum of its parts, new properties emerge when thoughts reach multiple individuals: scale enables unintended consequences through emergent properties.

Knowing these attributes, let’s look at our simplest use case: a causal thought within an individual. This correlates with a large object moving at slow speeds, relative to nanometers and the speed of light. These fall under the reign of Newtonian classical mechanics and its laws of motions and kinematic equations.

Let’s begin by applying Newton’s Laws of Motion to the mind.

Newton’s First Law of Motion: An object at rest remains at rest, an object in motion remains in motion at constant speed and in a straight line unless acted upon by an unbalanced force

If we remember that thought is our object at hand, we can see the law of inertia applied in many ways.

In a physical context, thought can be described as the motion of an action potential through a group of neurons. Applying Newton’s first law of motion, we can reasonably assume that those who tend to think, make a habit out of it. In other words, how we approach thinking is habitual - whether that’s doing before thinking, critically thinking, or overthinking. The physical electrical impulses of the brain follow the same track unless acted upon by a new force.

As we previously discussed, thoughts have psychic origins as well as physical ones. Like the physical origin of thoughts, the psychic origins tend to be dictated by similar habits: what you consume. As the saying goes, you are what you eat, but if we modify this adage for the psychic context, you are what you pay attention to. If you scroll social media in your spare time, your brain becomes ingrained with the content of your favorite influencers and you develop a lust for more short form content - a habit is born.

Secondly, the content of thoughts are habitual. Thought patterns can be described like roads - as a path gets more traffic, the government tends to respond by increasing its capacity. Naturally it is more efficient to drive on a freshly paved 8 lane super highway then it is to ride along a dirt backroad. The things you think about burrow a neural path in your brain that is habitually followed in the future, further ingraining the path. A feedback loop of supply and demand is born.

Lastly, the output of thoughts are habitual. We can discard them, let them ruminate to no end, or willfully translate them into action. And unless we do something about it, we will follow whichever of these tendencies we gravitate towards on auto-pilot. Of course, different situations call for different outputs, which increases the need to be mindful of the approach we take.

Our behavior can be described as a series of interlocked feedback loops driven by inertia. All of the above feedback loops require conscious effort to change - otherwise they continue on, burrowing deeper in our psyches as we remain blissfully unaware. Napoleon Hill called this psychic inertia hypnotic rhythm in Outwitting the Devil. Carl Jung has described the same idea in different terms:

“Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.” - C.G. Jung

Newton’s Second Law of Motion: Force = mass * acceleration

One of the most prevalent forces we experience is gravity. Every muscle, bone, and cell in our bodies have adapted to this force - the body perseveres in spite of a force pushing us into the earth at every moment of our lives. This becomes apparent by observing the health of those living in the absence of terrestrial gravity. Returning to the context of Newton’s Second Law, our weight is equal to mass times a constant acceleration since we all live on a planet with the same gravitational acceleration. In a terrestrial world, weight is solely influenced by our physical mass.

Like the gravitational pull on our bodies, we all experience a psychological weight that depends on the amount of mass our minds carry. Being human, we all cope with this psychological weight.

Psychological weight can be broken down into three categories:

Weight of our responsibilities

Weight of our existence

Weight of our emotional baggage

Our responsibility to others is a weight that varies widely depending on our situation. The primary effect of this psychological weight is the creation of boundaries in how we live. The author has argued we all carry a minimum duty to do no harm to mankind, so that creates certain boundaries in how many behave. If we take this duty seriously, we obey traffic laws that ensure the safety of others, refrain from committing violent offenses, and avoid fraudulent behavior - even if the contrary would benefit or convenience us.

The mass of responsibility fluctuates based on your personal context. Have children to provide for? Stability is more likely to be a guiding principle even if you crave the freedom of a nomadic lifestyle. Perhaps you have certain talents you believe you owe to others. The requisite hours of practice mastering your craft can limit your time for leisure activities. Life can feel richer when we embrace responsibility, yet it can feel crushing, even suffocating at times.

Responsibility can add richness to our lives since it can alleviate our second psychological weight: the weight of our existence. This refers to those questions that nobody can definitively answer with empirical evidence: Why are we here? What is the point of existence if we must die someday? What happens after we die? Because there is no proven “right” answer, these questions can be highly agitating and leave us all with a psychological weight. What am I specifically here for? How do I know if my life was meaningful? By embracing responsibility to others, we can see some of these questions lose their weight - I’m here to serve others, I can tell my life was meaningful based on the impact I’ve had on my loved ones.

The weight of existence is dependent on your values: Do you embrace your responsibility to others? Do you subscribe to an organized religion or philosophy that provides a sense of significance? Do you seek humor and embrace play to bring about lightheartedness? Perhaps you distract yourself from the weight of existence through excessive consumption of vices like alcohol, social media, or television.

Excessive consumption is also used to address the third weight: the weight of emotional baggage. This refers to the psychological burden associated with regrets, trauma, insecurity, and shameful thoughts. Emotional baggage is highly dependent upon your experiences and your beliefs about those experiences. Those with a childhood that involved death or abuse are more likely to carry emotional baggage than those with a pleasant upbringing, and those that found a way to productively cope with such experiences carry less emotional baggage than individuals who ignored Jung’s advice by letting the unconscious fester and dictate their fate.

Our past experiences that create emotional baggage are largely outside our control, yet the way we cope with them remains within our control. Embracing a philosophy that separates the world between what we can control and what we cannot has helped many people ease the weight of baggage despite objectively unpleasant conditions, and it explains why some are able to rise above their past while others wallow in despair.

Regret may be the exception to this notion that our baggage-inducing experiences fall outside our control since regret usually stems from a choice we made or action we didn’t take. Perhaps this is why regret stings the most - it falls solely on our decisions and there is no real way to cope besides through ruthless accountability for our choices paired with self-love - a difficult balance to find.

Some psychological weights become too burdensome, so they drag us down and sink us into a depression. There are only two ways out of this equation. We can either decrease the weight we bear or increase our ability to withstand psychological stress.

This dilemma resembles the myth of Icarus in which his father warned him to not fly too high nor too low since both would lead to a depression into the ocean with no return. This has largely been interpreted as a cautionary tale to avoid the ilk of hubris and complacency.

In the context of Newton’s Second Law, excessive hubris looks like shedding too much weight and floating so high that our wings catch on fire, hurling us back into the ocean. It looks like someone who sheds all responsibilities and does whatever he pleases, regardless of how it impacts others. With the hubris of a narcissist, this approach is rooted in the belief that we can float above our psychological weight presented by our responsibilities, emotional baggage, and the absurdity of existence itself. Milan Kundera explored the inevitable and ironic psychological weight such a philosophy imposes in The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

Excessive complacency shares the equally bleak fate as flying too high: drowning. Complacency is embodied by a feeling of hopelessness in which an overly burdensome psychological weight is accepted - weight is not removed but strength is not built. An example could be a young man’s longing looks in the mirror, pining to look like Schwarzenegger yet leisurely exercising. The psychological weight of the lofty unfinished goal slowly crushes the complacent soul each time the bearer goes through the motions of life without any intensity.

Despite a similar appearance of bearing a hefty burden, this is dramatically different from actually building resilience. Complacency describes physical presence yet spiritual absence - a passive approach where life just happens to individuals, where one copes through dissociation rather than engagement with their burden. Like the bodybuilder that must learn to embrace physical pain to build physical strength, the mindbuilder must embrace the psychological pain associated with the weight of their life to build psychological strength.

Balancing weight is a fine art especially since we don’t pick many of our responsibilities, experiences, nor the weight of our existence. It is up to us to understand what weight we bear, what weights we can alleviate, and the amount of psychological weight we are capable of bearing. Unlike Icarus, we must find our path to fly above water without soaring too high.

Psychological weight is only one type of force. In The Three Body Problem of the Mind, the author explores the gravitational pull of three fundamental desires: hedonistic pleasure, individuation, and duty. The force these desires exert on us ultimately depends on two factors surrounding mimetic desire: the mimetic potential of a fundamental desire and our distance from mimetic models espousing the tenets of a specific desire. These factors correspond to mass and acceleration, which create a gravitational force on the mind.

The mimetic potential of a desire or its ability to propagate depends on a few factors, the first being susceptibility to an espoused desire or your personal context. If we viewed this through a marketing lens, an idea is the product and the messaging around it is the marketing material. The goal of an evangelist is to find their target audience - or those most receptive to the idea - and spread the message to them. Thus the likelihood of an idea propagating or taking root within you depends on whether you are the target audience and the strength of the marketing. Another way to look at it is through the lens of immunity. An idea is like a virus and its likelihood of spreading to a new host - who spreads it to additional hosts - depends on if you are the target host. For example, a bird flu may infect your parakeet but not your dog. Viral infection also depends on the strength of your immune system - how well equipped are you from preventing a virus from taking hold? There is value in knowing what ideas or mind viruses you are susceptible to - whether by knowing which type of ideas target you or the strength of your intellectual immune system.

The second factor - distance from mimetic models - is much more straightforward. If you surround yourself with people engaged in hedonistic behavior, you will probably feel a stronger pull towards it. Likewise, filling your free time with a podcast on parenting will pull you closer to your duty towards your children. This is the old adage that you are a combination of the five people you surround yourself with the most.

Like many equations of The Physics of the Mind, the mimetic potential and proximity to mimetic ideas are highly difficult to quantify, yet they remain valuable as directional transfer functions if we reflect on our susceptibility to certain types of ideas and our consumption habits.

Newton’s Second Law informs us that there are many forces acting upon us, but unlike physical forces, we have a greater degree of control over the factors that influence forces like psychological weight and desire. It is our job to find the right balance of these forces whether that’s by adjusting our responsibilities, our mindset around these responsibilities, how we carry emotional baggage, the mimetic models we keep close, or improving our intellectual immune system.

Newton’s Third Law: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction

The subtext of this law is that the world is governed by cause and effect. As we peel back layers of the causal onion, we find that many actions live within a feedback loop that create a reaction upon the actor. To better understand how feedback loops influence others and ourselves; we can start by identifying the cause and effect of different actions.

Observing the effects of your actions is much simpler and more reliable than inferring causes, so we will start here. Observation requires you to simply pay attention and identify trends. “When I eat Chick-Fil-A, I tend to feel sluggish.” “When I exercise frequently, I feel mentally sharp and more relaxed.” Such self-reflection is the simplest way we can identify trends in effects since the only dependencies are the actions you choose and your resultant feelings. You merely observe your internal state.

We can add a layer of complexity by observing the effects of interacting with others. “When I dress nicer, people tend to treat me with more respect.” “When I don’t ask acquaintances questions about their life, they tend to be less interested in me as a person.” This adds a smidgeon of complexity since it requires you to step outside yourself and pay attention to what others are doing. These observations tend to be influenced by your identity and the beliefs you hold about yourself.

Thirdly, we can observe the effects of others interacting with each other. “When someone is rude to another, it is generally returned with hostility.” “During periods of distress, people tend to sacrifice ideals for their self-interest.” These observations tend to be filtered by the biases you hold about others.

Effects are simple enough since they require observation as time passes by. Cause is a little more difficult since it requires us to work backwards in time. This isn’t overly complex either since it requires basic skills: Asking why and formulating a hypothesis to explain why. The difficulty lies in creating a hypothesis that has some grounding in this world of cause and effect. Fortunately, we can rely on observation to validate whether an activity does indeed cause an event to occur.

After observing similar effects from the same action or cause enough times, we can connect them together into a system or mental model. When effects start to stack into causes in a feedback loop, we see a cybernetic system emerge that remains in motion unless influenced by an outside force per Newton’s First Law.

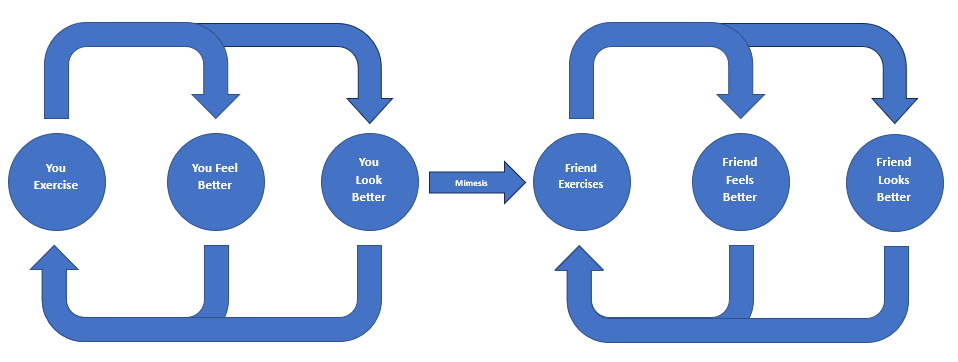

These feedback loops can also be catalysts to additional feedback loops. For example, let’s say you are in an exercise centric feedback loop. In the short term, daily exercise makes you feel better, reinforcing this desire to exercise. Within yourself, a highly predictable loop of cause and effect is born - actions lead to reactions. Over a longer period of time, you see your body transform in a positive manner, so much so it is noticeable to others. The satisfaction from looking in the mirror and positive commentary from friends further reinforces your desire to exercise. Your inner feedback loop continues stronger than ever, yet it kicks off another feedback loop. Friends, driven by inspiration or jealousy, embark on the same journey you started six months ago. Hence your feedback loop spawned off a few others like a hydra reproducing through budding.

The takeaway from this discussion on feedback loops is what Maximus declared to his soldiers in the film Gladiator: “What we do now echoes in eternity.” This is true in ourselves through the Newtonian First Law of Inertia as well as his Third Law: everything you interact with leaves an imprint upon yourself because it kicks off feedback loops that return to you. In a world of complex feedback loops, the Newtonian equal and opposite reaction to your action is not a matter of if but when. Curious enough, the ancient Indians discovered this law well before Newton through the concept of karma. Perhaps it holds such a spiritual nature since we cannot effectively predict or map the ways our actions return to us.

In exploring the application of this Newtonian law, the author’s largest takeaway is that certain activities are good for us even if there is not a direct benefit from it. Reading is good for you even if you don’t remember all of its contents because what you read shapes who you are. Maintaining relationships without considering them as a means to an end is valuable since the hospitality you extend may return to you in unexpected ways and again, they shape who you are.

As in the physical world, Newtonian physics starts to break down in highly complex systems, so we cannot solely rely on such systems built by causal observations. The Three Body Problem is one example in which we cannot rely on Newtonian physics to make adequate predictions - it leads us to spin our wheels at best but at worst, reliance on these mental models can lead to a false sense of understanding. The world is not strictly governed by Newtonian physics, hence it does not conform to absolute models, which Edward Lorenz demonstrated by relating how a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil can disturb his weather predictions in Texas.

We can reap the benefits of systems thinking while avoiding its pitfalls by embracing the Socratic method to continuously question our beliefs and the scientific method to put them to the test. A simple exercise in the Socratic method involves taking any belief or observation and continuing to ask yourself why. Do this a few times and you may be surprised at what you converge upon. More pragmatically, the guidance given to engineers attempting to understand a root cause through a Five Why analysis is to stop once you’ve reached the furthest cause that remains within your influence. We can leverage this approach for our more pragmatic problems as well. Such exercises can shine a spotlight on our beliefs which enables us to challenge them in a scientific manner, and the scientific method enables us to challenge whether a cause and effect relationship exists. When we propose a cause (hypothesis) to certain events, we can observe the results and decide whether they falsify the results. Such trial and error enables us to refine the mental models and systems we have identified.

Of course we will never be able to test every condition in a reproducible manner, particularly when highly variable human minds - both in the sense of how our internal states change and in the sense of variability between different minds - are the subjects. In Part 3, we will explore how quantum mechanics, relativistic mechanics, and quantum field theory offer some ailment to this predicament.