Not too long ago, I wrote one of my favorites essays - a discussion on how context clarity is a prerequisite for the pursuit of principles, beginning with the recognition that the validity of information is context dependent. In other words, the nearby circumstances influence whether a piece of information is true or not.

It wasn’t until now that I came to realize why that is. Context dependencies enable holism or sight of the big picture. In a complicated system, the way the parts interact with each other is more informative than the function of each part. This is because of a phenomenon called emergence. The emergence of new properties arise when the interactions between parts reach a certain threshold of scale and complexity. An example is the transformation of a series of gears into a tool that can tell you the time.

These properties can emerge spontaneously or by design. Our watch filled with gears emerges by design, but spontaneous properties emerge through unintended consequences, which spring up more and more in an interconnected world. As technology develops, we become more connected at an accelerated rate, which means emergent properties will dominate the shape of our world more than a mere part.

Reductionism is a form of context tunnel vision that ignores these truths. It is the belief that the whole is equal to the sum of its parts. It fixates on the function of parts while ignoring the interaction between parts. Reductionism looks like the use of a magnifying glass to study brushstrokes in an attempt to understand the message of a painting. Without stepping back to see how the brushstrokes meld together, there is no way to see the bigger picture.

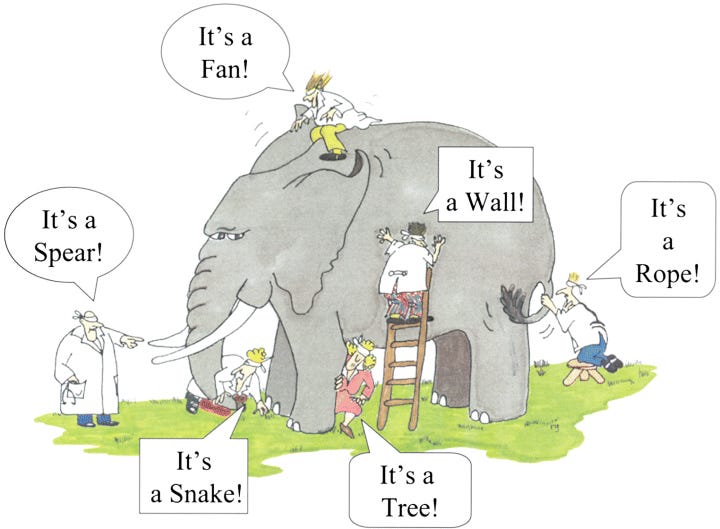

Ask a reductionist how to find the big picture and they’ll tell you to form a committee of specialists. These specialists - assuming they are of the reductionist variety - will miss the big picture because they fail to account for emergent properties.

This reductionist committee resembles our Western culture where people are encouraged to leverage their unique knowledge to solve the most niche problems. Instead of trying to be the best at something many people need, many try to be the best at something only a handful of people need. Everyone wants to be a big fish, so they all live in their own little ponds. The chase of this unique pond with specialized knowledge may be because of a multitude of factors:

The need to feel special

Collective reductionist views

The former is the idea that a childhood upbringing filled with accolades and reassurances of specialty bleeds over into adulthood choices. Why try to be the best in a big pond when you can be the big (and only) fish in a special small pond just for you? Boomers have worn this argument out and it isn’t worth exploring much further besides to say it is likely a factor that led us towards our hyper-specialized society.

The latter suggests we are collectively the reductionist that suggests a problem be solved by a committee of specialists. A potential explanation for this is that for most of human history, the whole has equaled the sum of the parts. It is only a recent phenomenon where interconnected parts and their emergent properties have, well, emerged. Hence, the reductionist worldview has served us well in the past, but we have reached a point where our beliefs must evolve.

Regardless of the reason(s) behind hyper-specialization and its focus on each part, it becomes a problem for two reasons:

It misses emergent properties

It misses the root cause of failure modes in complex systems

As we previously saw, our reductionist committee of specialists would struggle to characterize an elephant because they are blind to the interactions between the parts. They fail to see how the parts interact with one another, which can lead to mistaken assumptions like the stock market is no more than a sum of investors, an economy is no more than a sum of businesses, or a watch is no more than a sum of gears.

The reductionist attempt to thoroughly understand each part in isolation is a challenge and lacking in scientific rigor when operating in an environment where the parts cannot be isolated (e.g. the economy, human body, etc.). This isn’t to say these efforts are completely worthless since not everything need be scientific. The problem is when the specialist attempts to call their study of parts that cannot be isolated or measured in a controlled environment scientific. This is by definition, pseudoscience.

These may sound like strong words, but we must remember the simple truth we expressed at the beginning of this essay: in a complex system, the behavior of a part is more likely to be influenced by its context. If the part is isolated from its context and a conclusion is extrapolated about its behavior in all contexts, a mistaken conclusion is inevitable. An example of this is a cardiologist who doesn’t know the limitations of his expertise. He observes a problem in the cardiovascular system and concludes that there is a problem within the cardiovascular system, which leads to the prescription of certain medication. But what if this problem is a symptom of a neurological problem? We miss the root cause and treat the symptoms. This is how symptom management has become so prevalent in the healthcare industry - there is no Boogeyman hiding cures from you to line his greedy pockets with endless symptom management. Symptom management is a simple consequence of an honest person approaching a complex system with a reductionist view.

All this debate about reductionism isn’t meant to diminish the role of the specialist. If the world was filled with generalist “big picture” guys, we would quickly collapse from incompetence. We can’t create the big picture without paying attention to the detailed brushstrokes. This essay is intended to argue that the balance between generalists and specialists should shift in a world ever-growing in complexity.

Historically, the value of the generalist has been largely non-existent. We could see this play out in larger businesses where generalist management roles were filled with les incompétents so they could do less harm via the Dilbert Principle. Now that there are more interactions between parts - especially with supply chains and business processes growing in complexity - someone who understands the interactions between parts more than the function of individual parts has a perspective growing in value. If we do not fill management and leadership roles with experts on such interactions between different parts, the business will quickly become familiar with Chapter 11 of the US Bankruptcy Code.

Conclusion:

Holism is a difficult pill to swallow since reductionism led us to where we are today. The ability to understand the interactions between parts is a muscle we need to collectively grow if we want to keep up with our ever-connected world, and the individuals who cannot see the big picture will be disadvantaged compared to their more worldly peers. We just have to ensure that the pendulum does not swing too far, that we don’t create a world of generalists that vastly outnumber the specialists. We need each other’s skill sets to solve the new problems we face. From here, there are two unknowns worth future exploration:

What is the ideal ratio between generalists and specialists?

Which skill is best suited for which circumstances?

Perhaps these are topics for a future essay. For now, the author can confidently plead ignorance on the answer to these questions until further reflection. What do you think?