Two Truths & Its Implications

A Syllogism on Our Collective and Individual Psychologies

Two truths and a lie is a fun icebreaker that helps us get to know each other. Maybe not as fun, but a way to see the world from the vantage of my mental real estate is through a game we’ll call: Two Truths and its Implications. Let’s explore a syllogism, shall we?

The first truth the author will attempt to sell you on is the ubiquity of context dependencies. Context is what gives life to all concepts, knowledge, and understanding; and like the sea, context swirls about in turbulence, taking different concepts to different places in time and space. Without these eddies of context, we are stuck in a dead pool of abstraction. In other words, context influences the validity of information and grants it meaning. By influencing the validity of information, context changes the identities we hold of ourselves and others - if we discover an apple allergy in ourselves, the apple transforms from a nutritious snack to a potential source of harm. Further, the author tends to be entertaining and boisterous at parties but introspective and serious when secluded in a writing session.

The second truth is simple to state yet difficult to grasp: the external world is a hologram of your internal world. Naval Ravikant shared this truth when he described the world as a mirror, “The world reflects your feelings back at you.” If you feel the world is an infarcted mass of misery, you will find evidence of this - perhaps through subconscious filtering of the experiences reflected by your retina.

Robert Anton Wilson personifies this concept by describing two people within you: What the thinker thinks, the prover proves. The thinker dreams up infinite possibilities while the prover sets out to find evidence to support the thinker’s beliefs. The thinker is akin to your ego while the prover is the subconscious process that manipulates the information fed to the thinker to protect his fragile worldview

This holographic truth can be observed in differences between interpretations of similar experiences. Two different people can read the exact same text and glean different messages from it. The only logical explanation for this is that their internal worlds influenced their perception of the text since the external stimulus is identical. Perhaps differing past experiences have influenced their relationship with the ideas presented or the author himself, thereby causing them to interpret it differently.

To lay the premise of our syllogism:

If the world is a reflection of our internal world, what does the prevalence of context dependencies say about us in particular and in general?

The Syllogism of The Particular

Just like how we can learn the meaning of an object or concept by understanding its adjacent context, we can learn quite a bit about a particular person if we know what is adjacent to abstract concepts within their mind - if we study their specific mental context. This idea lends credibility to Jung’s association method, which is a simple way to gain insight into someone’s internal context by presenting them with an abstract concept.

His method is simple: Jung would present a word to a patient and instruct them to respond with the first word that came to mind. The assessment was both quantitative and qualitative in that he would assess delays in responses in addition to the responses themselves.

Quantitatively, he reasoned that a longer delay in response indicated something impeded their natural reaction - that the mind did not want to reveal its true association or intense emotions clouded a straightforward response.

Qualitatively, he unearthed different “complexes” by observing trends in results. If a cluster of words produced delays, the responses themselves were worth assessing. One example he shared was a married woman continuously pausing when presented with words like “false” “content” and “love”. Through later discussions they unearthed that she was not content with her marriage and felt false because she fantasized about leaving her husband.

Similarly, if a series of seemingly unrelated words produced similar associations, Jung would key in on this. One of his patients who was small in stature repeatedly answered “short” to seemingly disparate words. Together, they unearthed this was a source of pain for him throughout his childhood and continued to affect him, especially seeing that his siblings were all much larger in stature than himself.

A surprising amount of information was demonstrably pulled with this method, including the extraction of guilt from suspected criminals. Further, he found that those with consistent emotional responses tended to have atrophied emotions and those that responded with definitions were either imbeciles or people with a desire to appear intelligent. Jung took the inverse of what the patient revealed in these experiments to find the underlying intelligence and/or psychopathic complexes.

Jung and his association experiments sniffed out and exposed where the brain’s natural tendency to deceive and deflect others arose. This manifested itself through delayed responses when presented with concepts adjacent to sources of fear, pain, and trauma. It also reared its head when the prover uses this as a prime time to prove what the thinker thinks. The thinker is fragile in his beliefs, so he needs the prover to continually reinforce them. When presented with the experiment, the prover reinforces the thinker’s identity, “You are indeed the smartie pants you say you are! I will prove it by responding to this doctor with the definition of each word so we can all marvel at how intelligent you are.”

The beauty of this experiment is in its speed and simplicity. Through observation of delays, the practitioner can catch sources of pain, trauma, and fear out in the open while the ego is unable to defend itself beyond a feeble pause. Further, the ask for rapid, one-word responses prevents the thinker from becoming engaged. In that nanosecond, the patient is reliant on automatic responses, so trends in responses can be evaluated to find what the patient strongly identifies with.

The association method shows that tapping into the internal context - both the qualitative and quantitative - is so informative, it can become an invasive view into the depths of someone’s particular psyche. Let’s retreat to the surface level of the general where we find the mind’s heuristics, stereotypes, and other mental shortcuts.

The Syllogism of The General

If the world is a reflection of the internal and context dependencies are so prevalent, it stands to reason that each person is only exposed to a slice of the whole pie. Since we are initially introduced to a concept in one context, we may infer it is true in additional contexts. For example, if I witness a homeless person armed with the generosity of his fellow citizens purchase liquor and cigarettes, I may assume that other homeless people squander their money on addictions as well.

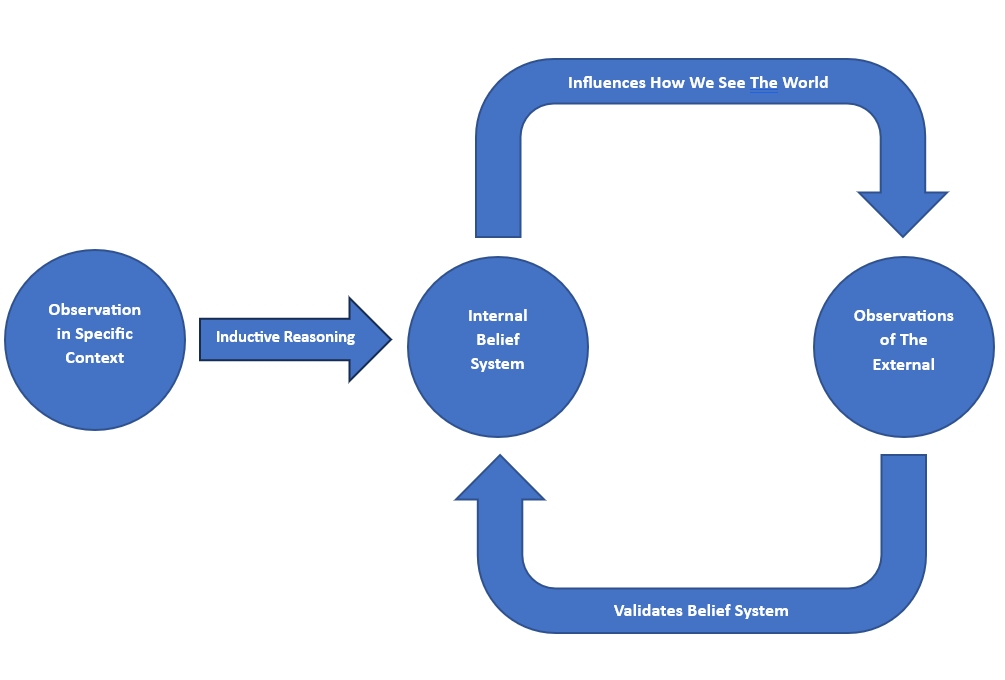

In other words, our worldviews frequently stem from specific experiences and inductive reasoning to broader beliefs. In a positive feedback loop, the worldview shapes what we see and what we see reinforces our beliefs. Essentially, we can easily become stuck in our ways if inductive reasoning kicks off a feedback loop between a belief formed from observation of narrow context and the external reinforces the internal.

This phenomenon should not be a surprising conclusion about general human behavior when we consider Newton’s First Law of Motion: a body in motion tends to stay in motion and a body at rest tends to stay at rest unless an external force is applied. Despite believing identities emulate quantum mechanics, I find our thought patterns obey Newtonian physics. The same thought patterns tend to stay in motion and reinforce themselves unless acted upon.

It also shouldn’t be a surprise since nature favors efficiency. An animal that unnecessarily expends energy dies off, so the most efficient survive. If we accept that evolution has led to the development of the human brain, we should expect the brain to be an efficient machine that conserves energy where it can, whether that’s through the aforementioned maintenance of the status quo or taking shortcuts. Through shortcuts, we find our susceptibility to the inductive reasoning that kicks off this feedback loop since a simple and useful worldview can be constructed with minimal effort when compared to a nuanced worldview that accounts for the world’s context dependencies.

Without awareness of these truths, we will continue to see the world narrowly and miss that multiple versions of truth can exist across different individuals. We continually assume that the truth shapes our beliefs rather than realize our experiences and beliefs shape our version of the truth. Until we step outside our own context, we will be trapped within our own universe and fail to meaningfully connect with others. To draw the obvious conclusion from this, we shouldn’t be surprised to see tribalism run rampant throughout human history.

To conclude our exploration of this syllogism on our collective and individual psychologies, I leave you with our original premise:

If the world is a reflection of our internal world, what does the prevalence of context dependencies say about us in particular and in general?

the original premise is a question. i think you give Jung credit for too much influence to the conclusion.

If the world is a reflection of our internal world, then the context that form my opinion, (experience), will influence my world view and my bias internal context will censor conflicting context that may challenge my internal view.

attributed to Mark Twain, " "it's easier to fool people than to convince them that they have been fooled"

concluded that i can not change. however knowing this, i can re-evaluate the exterior context and alter my view.

in fact, every one will do this after a new traumatic experience.

jmho

also because i find this subject interesting, not because i know anything about it.

i want to know how the public mind establishes context and conclusion.

our experience can be manipulated, out context may be propaganda more than experience as a public mind. and we want to 'fit in with our peers and neighbors, so we will hide our true thoughts and then hide the thoughts from our self as well.

and i could go on. . . .

thank you